Such a great feeling, that moment at the start of your holiday when the doors are all finally closed and everyone’s buckled in and the plane begins its push back. It's the lights turning off in the office, the calls coming to a halt, the doors swinging open at the end of the school day, it’s liberation. Barefoot in the sun.

There’s another moment that has a wholly different feeling, altogether more intense, not so carefree, but still a kind of happiness, as your ambulance reaches the driveway of the hospital, makes its way slowly towards the loading bay and reverses in.

However bad things may be, you have the comfort of knowing that you’re now in the hands of people who will know better than anyone what’s wrong, what you may need, and what can be done.

I have taken that ride when I was in danger and also when it turned out there was no danger at all, but there will always be a reason you’re on a gurney and it won’t be trivial, and you will always be deeply grateful.

The notion that it might not be there when you need it, that you might have no one who can see you, give you the care you may desperately need is too awful to consider. Imagine it happening to someone you love, imagine it happening to anyone.

Imagine it actually happening.

I quoted this earlier in the week, it bears repeating.

We’re just holding on, ICU nurse Michelle Rosentreter told Peter Fitzsimmons for the Sydney Morning Herald last week, nothing in our studies ever prepared us for this, and not even the most experienced of us have ever seen anything like it.

She said, usually, when you intubate someone and put them in an induced coma, you say ‘we’re just going to put you to sleep, and wake you up in a few days’. But with COVID patients we can’t say that because we don’t know if we can get them back. And they know that.

Fitzsimmons asked her if the rate of fresh infections in a day should keep lifting from the current to 1000 to say, 1500 or worse, could they cope? She told him,

I can honestly say we can’t. We are at breaking point right now.

In hospital earlier this year, I was kept in isolation, initially in one of the negative pressure rooms, while they waited for test results: Rhinovirus, it turned out, not Covid. But because I was infectious I continued to be treated in the cumbersome way that isolation requires and watching that made it very evident how much harder an outbreak would make everything for a system that is already hard-pressed.

We know, because we've been told this week, that we don't have a whole lot of ICU capacity compared to, say, Sydney.

God, Sydney. You hope fervently that what they’re doing - call it strategy, call it capitulation, take your pick - will not open the door to something terrible, and that they will be able to cope.

But you also look at the growing numbers and you hope for them that they’re not approaching something as grim as parts of the USA where people have been dying for want of available care.

She told him I can honestly say we can’t. We are at breaking point right now.

You'd think it would be chastening to read such a thing, that everyone's thinking would just lock on to doing everything possible to protect the hospitals, and the people who may need them. And yet the drum beat goes on for learning to live with the virus or facing the virus, to let interrupted life resume.

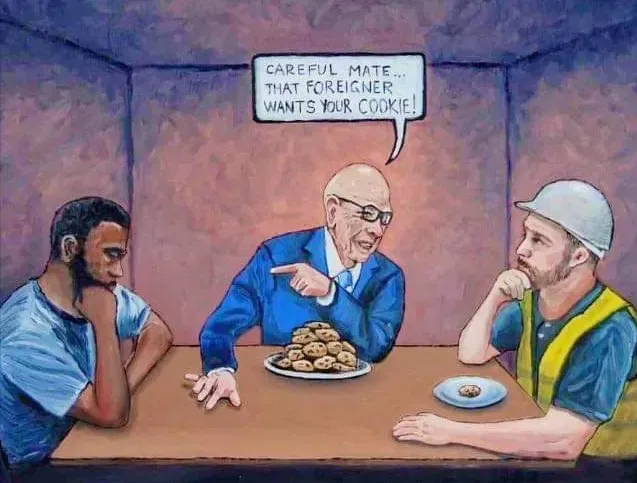

A couple of Australian tourism bosses, one of them Flight Centre founder Graham Turner, were in the the media today suggesting wide, hard lockdowns will be only used by authoritarian regimes in future pandemics; that while most of the world has come to its senses, Australia and New Zealand need to wake up; that the second-order effects of trying to save ‘some lives’ are enormous. Visiting here in May, Turner - Newshub reports - said of ramping international travel back up:

the odd person will die but we should focus on the positive things rather than their deaths

The intransigence of people who find the interruption of their highly agreeable life inconvenient and disagreeable is really quite breathtaking. Also cavalier. Even if you don't care about another living soul, the infectiousness of this thing must surely give you some pause.

This mother’s account in the Herald of her son’s experience could not make it more abundantly clear: the virus is ridiculously easy to catch. If he had caught Covid, where or how did it happen? Eventually they located a potential exposure site that coincided with his movements.

On the previous Sunday between 1pm and 3pm he had walked through West City Shopping Mall in Henderson and to the Countdown supermarket to buy crispy noodles, gummy worms and an energy drink. At some point he inhaled the aerosol of a Covid-infected person

I wrote a while ago about the whole notion of change, and what we might do when we find our lives upended. There are always possibilities. What's coming next may not be at all what we planned or expected or were hoping for, but that doesn't mean we can't find our way forward.

Maybe it will be possible, some day coming, for us to pick up where we let off. And maybe it won't. If that requires life as we know it to be adjusted for good, be it in smaller or altogether larger ways, then fine, let's work out how best to do that.

Given a choice between sucking it up so we can give life as we knew it a warm embrace, or rearranging ourselves so that our hospitals are protected, I opt for protecting the hospitals every time.

Whatever arrangements we make, please can our first question be: what's required to ensure the hospitals are there for us when we need them?

We all want our holidays, sure. But just as much - and maybe a whole lot more - we also want to know the ambulance will have somewhere to take us.

Loading comments...