Now that we've got all this DNA testing, so many people must be discovering that their family trees are utterly bogus. Because, you know, people's parents weren't actually who they thought they were.

Lindsey Dawson is saying this over coffee in the seaside village, where we're talking about her newest book.

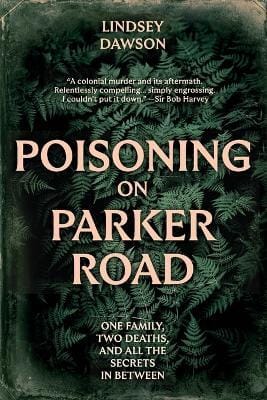

Poisoning on Parker Road is the title — one family, two deaths, and all the secrets in between — and it has a whole bunch of my favourite things: early Auckland, family trees, unexpected twists and turns, a search for patterns in the randomness of life and death.

It begins with a murder in Oratia, a long ride in those days from town. Town was where a person might go to buy strychnine or some such, might bring it back to feed to a man he calls friend.

Don't want to give away too much about a Victorian murder mystery, obviously, but let's just say there's also a wife, and infants, and very questionable actions, and when it’s all over one man is dead, another is swinging from a rope and the wife in the middle — well — we still don’t know her part in this for sure, but we can go right ahead and guess. It appears the judge does, at any rate, when he describes her as a woman lost to every sense of decency

It's quite the moment in 1890s Auckland. The ladies’ gallery in the courtroom is crammed, reporters are given tours of the condemned man's cell, there's a pretty strong sense the verdict's in before the trial even begins.

The widow Alice is never called to testify. She’s absent from the entire proceedings, but also present in all of it.

And then it’s done and we're following the children and, in due course, the widow back to England. Can you imagine, Lindsey asks, facing her family and her husband's family. Can you imagine what that conversation would have been like?

What became of them all? The more she pulled the more she found, little things like the family's cleft chin becoming a genetic marker traced through generations, larger things like a huge box in an English attic, full of records. Not everything emerged readily, though. A baby book she discovered had one side, the Italian side, maternal side of the family carefully documented while the other remained blank.

She talks of the power of silence in families; the lasting wounds of family secrets. Often a dead silence falls after there's been a crime and something that people are embarrassed about, or a generation later, you know, after it's not being talked about, another generation goes and then nobody even knows anything.

So easy to go down rabbit holes, so easy to keep pulling at threads. By the end of it we're talking about the rules of assisted dying in the 21st century, to give you an idea of the very long arc of a tale that grows ever more fascinating.

So many people must be discovering that their family trees are utterly bogus because people's parents weren't actually who they thought they were.

The genealogy business is now worth $5 billion a year, expected to keep growing to $15 billion. It's a lot more than just family trees, you sense. We talk about adoption stories with a happy ending; about adoption stories with only more hurt. We talk about what it meant back then to uproot from England to New Zealand, like going to Mars now.

I have been pulling at threads too, was going to report months ago about what I’d found about my forebears but keep finding more, still making more sense of the what was on your mind when you came here? and who were you?

I’ve found I can’t let go of the notion of the last time someone says your name out loud.

Last visit I pulled out the laptop to show Dad all the photos of churches and cemeteries and farms and houses in Cumbria. He’s the one who first told me: Our people came from Cumbria.

Where's that? he asked, admiring the fine farm land.

Cumbria, I said.

What’s there? he asked.

That’s where our people came from I told him, saying the names out loud of his father and the ones before him.

I want to get it all down. I hope I might get it all down while he’s still here for it.

What do I want to get down? Answers to the same questions over and over: What was on your mind? Who were you?

Our reckoning with mortality moves along as we do.

Lately I’ve been seeing kids in the street and the playground and thinking, You'll still be here when it’s 2100. I know I won’t be. Not in self pity, just in a sort of small awe and goodwill.

Not only Who were you? but also Who will you be?

Our reckoning with mortality moves along as we do. I hope so, anyway.

Dad got sick a few months ago and the ambulance came for him.

He was his usual cheerful self to the paramedics, but there was a moment of greater candour than the usual affable banter when they asked him how he was doing: Well I miss my wife, he told them.

My sister stayed with him overnight in the hospital. At one point, full of antibiotics and suddenly bewildered to find himself in an unfamiliar bathroom in the middle of the night, he asked her, Am I dead?

Maybe I’m writing this for him, and for me, and to make some more sense of the randomness of life and death.

Maybe I’m writing it for someone in 2100.

Just a note about Substack and the Nazi problem.

I got started on moving to Ghost last year but life got in the way. On top of that, it's not just a flick of the switch if you want a full clean move, so I also got diverted into resuming my own server. And then I marooned myself on indecision.

What I'll probably do is move to Ghost for now, but I’ll talk about it more fully once I’ve got things resolved.

The aim is to do it in a way that you’ll just go on receiving your newsletters with the same subscription without having to do anything. It can be done, so that’s what I’m aiming for. I’ll keep you posted.

And, as ever, thanks so very much for your support. I truly appreciate it.